Providing financial — and increasingly nonfinancial — information for decisionmaking is one of the most important reasons for the finance function’s existence. Consequently, falling short in management reporting creates risks for the organisation: Failing to provide timely, useful financial information means that decisions will be based on misleading, inaccurate, or even meaningless information. It hampers key internal decision-makers’ ability to lead the organisation successfully.

Finance teams have numerous opportunities to inadvertently deliver useless and misleading reporting for executives, board members, business unit leaders, and other key internal decisionmakers.

Here are significant mistakes to avoid (see also the sidebar, “Data Visualisation Risks”).

Information that’s not timely

The easiest way to fail at management reporting is not reporting in a timely way. The further an organisation travels obliviously into the future without its decision-makers knowing its key performance measures, the greater the risks to the organisation.

Though the information captured in the general ledger and other systems inevitably looks backwards in time, it can still provide insights into performance and trends that enable decision-makers to monitor activities and make real-time adjustments. But decision-makers need to see it in a timely way. The bigger the time gap between past results and current decision-making opportunities, the greater the risk to the business as leaders miss opportunities for quick course changes.

When closing the books monthly, reasonably accurate estimates can be effective for decision-makers. It is important to not waste time ensuring the accuracy of minutiae that may not be material to the overall results. Insisting on extra time to perfect the financial results can prolong decision-makers’ reliance upon guesswork.

Information that’s not useful

Even if you and your team deliver management reporting in a timely way, that doesn’t mean that what is delivered is necessarily useful to decision-makers.

If those decision-makers took time to define for you what they consider useful, the list would likely include these characteristics as a minimum: reliable; understandable; and having the optimum level of detail, ie, they are concise yet complete.

And it’s not unusual for the normal management reporting that finance provides to fall short in some — and sometimes all — of those three attributes.

Reports that are not reliable

If the finance team doesn’t exercise due care, decision-makers can lose confidence in management reporting and cease to rely on it. And this often occurs in two stages.

The first stage involves inaccuracies in the information reported, with risks of that occurring at each stage of the management reporting process:

- Gaps or errors at the general ledger level (US GAAP or IFRS applied incorrectly, entries made incorrectly, material entries overlooked, ineffective end-of-period cutoff procedures used, etc.).

- Errors within the standard reporting packages from the accounting systems (misleading captions and categories, reports out of balance, etc.).

- Errors translating those system outputs into spreadsheet-based reports for the decision-makers (errors rekeying data, formula errors, hidden data, rows and columns that don’t foot and cross-foot, etc.). The flexibility inherent in spreadsheet tools makes this last step in the process especially ripe for inaccuracies. These inaccuracies take lots of work to identify and correct because so many of the problems lie in hidden rows or complex formulas within individual cells or hardcoded data mixed in with formulas.

But the second stage is more subtle and pernicious: If internal decisionmakers encounter inaccurate financial information regularly in the management reporting they receive, they will lose confidence in and cease to rely on any management reporting. Reliability results from recognised accuracy delivered over time.

Reports that are not understandable

The finance team must ensure the financial reports it produces are understandable to the intended audience. Board members may not understand jargon and specialised acronyms and abbreviations. The board members’ lack of day-to-day involvement in the organisation and, for some, a lack of familiarity with specialised language and management’s communication shortcuts make them particularly vulnerable to misunderstandings. This puts them in the uncomfortable spot of needing to ask for clarification.

But often the unfamiliar language that bedevils directors combines with the following mistakes that regularly baffle all decision-makers — board members and management alike:

Ambiguous report elements

Decision-makers can get lulled into complacency by the familiar format of captions down the left, headings along the top, and parallel columns of numbers in the body of the report. Lack of attention to several common mistakes can cause problems, eg, where headings and captions are unclear; time periods or dates are unspecified (or only partially identified, such as “Q1” — but of which fiscal year?); a failure to distinguish between actual, budget, and forecast data; and, in a report on a multi-entity organisation, leaving the specific entity unstated.

Technical references

Finance professionals inhabit a complex and heavily codified world of financial reporting standards and tax codes and possibly of specialised regulatory knowledge. Technical language and code section references to technical compendia obscure valuable information. A simple layperson’s explanation alongside the technical terminology can help dramatically.

An inappropriate level of precision

The risk here relates to reporting large currency amounts with meaningless and distracting significant figures (billions of dollars of assets reported to the nearest penny, for instance), or rounding small but material numbers at a level that obscures significant variations (eg, return on assets rounded to the nearest 10%).

Zero context

This is all too common. Reporting financial information in a timely way, accurately, with unambiguous labels and without specialised or technical language can still deliver useless information by excluding appropriate context. For example: You report that “Days sales outstanding in Accounts Receivable” at month end came in at 46. You’ve done your job; you’ve reported on financial results. Yet decision-makers may not know how that compares with your organisation’s results over time (trending better or worse or largely unchanged?) Or with your peers or the industry average. Context is too valuable to decision-makers to neglect. It needs to be a normal part of your financial reporting.

Reports without an optimum level of detail

Decision-makers become emphatic on this next topic, regularly insisting you provide them the Goldilocks dose of financial reporting: not too much, not too little, but just right.

This creates a risk related to swinging toward either extreme: providing decision-makers only highly summarised basic information or deluging them with details. You may be swamping them with minutiae in an attempt to demonstrate transparency and thoroughness. But by showing them so much information (perhaps thousands of pages for a monthly board pack), you are effectively revealing very little. Meaningful, material, and actionable information readily gets lost in a profusion of data.

So many risks

Without due care and attention, a finance team can inadvertently deliver near-zero-value management reporting: both late and not useful. And, not uncommonly, a failure to provide useful information stems from inattention to all three usefulness aspects: reliability, understandability, and providing neither too much nor too little information.

Failing in even one respect — whether in timeliness, reliability, understandability, or appropriate volume — can yield significant challenges for decision-makers and thereby undermine the organisation’s success.

Data visualisation risks

Data visualisation commands much attention. Decision-makers ask for it to help them understand financial data. However, finance teams often deliver visualisations that make it harder for decision-makers to understand the data correctly or easily.

Key visualisation risks include:

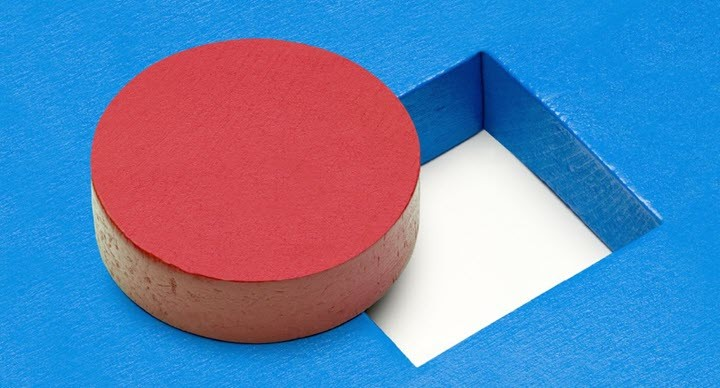

Utilising a chart type that doesn’t fit the data

For example, a pie chart or doughnut chart doesn’t accurately display time series data. Likewise, a line or area chart — both of which imply data across time — would not accurately present data that does not have a time series element.

Manipulating the range of the vertical axis

This is especially risky for trend data. For data where minute changes are significant (fractions of a percentage point in return on assets, for instance), using zero as the lower bound of the range for the axis obscures significant changes as they occur, making them appear tiny, if they can be discerned at all. And for data where day-to-day swings don’t matter as much as general trends, narrowing the range (setting the lower bound well above zero) creates a perception of wild, volatile swings and obscures the general trend by drawing attention to the immaterial day-to-day variations.

Combining too many data elements in a single chart

Some readers of financial information have trouble processing more than a handful of patterns at a time. This problem is exacerbated when charts are loaded with too much data, such as too many data series. Also, Excel lets you show data relative to two vertical axes in line and area and column and combo charts. This amplifies the “too many patterns” risk — especially if decision-makers struggle to decipher which data series goes with which axis.

Getting fancy

Options for formatting creativity abound. This is not the time to indulge your creative instincts with a profusion of colours, highlighting, bolding, different text sizes, shadows, callouts, and so on. And be extra careful with the more obscure chart types, like scatter graphs, radar graphs, or box-and-whisker graphs, as they can be hard to understand.