As Wall Street rallies on hopes for interest rate cuts in 2024, the real world is still coming to terms with the full weight of central bank tightening.

Over the past two years, money has been squeezed out of the market by central banks fighting to get an inflation surge under control. That’s made borrowing more expensive for governments, corporates and consumers, and will keep denting spending well into next year.

“The bottom line is that the Federal Reserve hikes are biting and will continue to in 2024,” said Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management. “Restrictiveness is not going away anytime soon.”

As higher rates ripple through economies, Bloomberg Economics forecasts that 2024 will be the weakest non-crisis year since the early part of the century. As huge debts mature in the coming years, refinancing may be too costly for some businesses even if central banks achieve a soft landing, leading to defaults and losses for lenders. Consumers are already finding credit much harder to access, while regional banks face a huge hit from souring commercial real estate valuations.

The question now is whether central banks, having underestimated the threat of inflation, will pivot too late to rate cuts to put a floor under the slowdown.

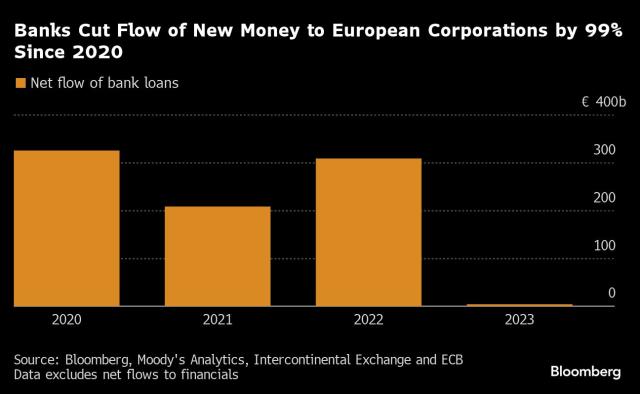

The charts below show the stresses facing debt markets as the impact of interest rate increases passes through to the real economy.

Analysis by Citigroup Inc. economists earlier this year found that the deterioration in credit availability shown in US and euro-area lending surveys could lower real growth in both regions by about 1% to 2% by the end of next year. Stuart Paul, an economist in Bloomberg Economics expects “spending in interest-sensitive categories to continue softening as the effects of monetary policy continue taking root.”

Some economists downplay the idea that the pain from tighter monetary policy will persist, while the pessimist camp of recession forecasters has shrunk.

Regardless, it’s been a particularly horrid time for households, whose income has been gobbled up by the soaring cost of goods and services as well as higher rental costs and credit card debt rates.

After two years of inflation, “it’s understandable that consumers have some trouble making ends meet,” Nestle SA Chief Executive Officer Mark Schneider said on Bloomberg Television. In addition, central bank tightening “is now making its way into the real economy. You see mortgage rates going up, you see leases and rents going up, so all of that adds up to a good deal of consumer caution.”

The squeeze on customers, particularly those with lower incomes, can be seen through credit card delinquencies, which have spiked above pre-pandemic norms, and the subprime auto delinquency rate at an all-time high.

“We’ve seen banks tighten their lending standards at a clip historically consistent with recession,” said Shannon Seery Grein, an economist at Wells Fargo & Co.. “Even once the Fed begins to ease policy, it will take time for the more accommodative conditions to roll through the economy and into consumer borrowing costs.”

Corporates are also starting to feel the pain of the uncertain outlook and squeeze on incomes.

Toymaker Hasbro plans to cut 20% of staff amid slumping holiday sales, while Ford Motor Co. is slashing production goals for its signature electric vehicle, in part because customers balked at high prices. On Thursday, Nike Inc. announced plans to cut jobs and said it’s seeing “indications of more cautious consumer behavior around the world.”

Earlier this month, Walgreen Boots Alliance Co. was cut to junk by Moody’s, which cited a weak consumer environment among other factors.

Strategists at Morgan Stanley, including Vishwas Patkar, say there will be more corporate bond downgrades “as the lagged impact of restrictive rates policy continues to feed through” and damages both the cash flow of poorly-performing companies and their ability to pay their debts.

Bank Failures

Although the Wall Street narrative is “nothing broke this year,” 2023 still saw the failure of a globally systemic bank in Credit Suisse, while a run on regional lenders in the US required the intervention of larger banks, the government and regulators to prevent contagion from spreading further.

The run on the banks came after losses on securities portfolios, while souring commercial real estate loans will hamstring many of those smaller lenders for years to come.

More than $2.8 trillion of US CRE debt is due to mature from next year through 2028, according to Trepp Inc., the majority of it held by banks. A 35% drop in office values there since the peak means lenders are looking at billions of dollars in losses that will crystallize as borrowers hand back the keys when their loans come due for refinancing.

Fitch forecasts US CMBS office loan delinquencies will jump to 8.1% in 2024 and 9.9% in 2025.

In a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research this month, researchers including Erica Xuewei Jiang said that “as long as interest rates remain elevated, the US banking system will face a prolonged period of significant insolvency risk.”

The lending backdrop has also shifted in the euro region, where banks have significantly pulled back from lending and are also facing commercial property losses.

Credit standards have been tightening as the deteriorating economic outlook damps lenders’ tolerance for risk. Banks are demanding higher loan margins as market rates filter through to the real economy, while borrowers are trying to reduce their debt rather than looking to take on additional credit to finance investments.

The move from quantitative easing to tightening by central banks has also hit credit conditions, a trend that lenders expect to continue into next year, sapping liquidity. That creates opportunities for private credit providers who, flush with cash, could trigger a race to the bottom on lending globally, resulting in systemic issues, Moody’s Investors Service warned in September.

The return of a bankruptcy cycle following the end of the cheap money era could also swallow up some CCC-rated bond issuers who were kept alive by lower interest rates during the pandemic. While the universe of bonds is small at less than $176 billion, it’s still well above levels during the financial crisis, when bankruptcies spiked.

Companies with that rating face substantially higher borrowing costs as their debt comes due to be refinanced, on top of a potential customer pullback that will slam their earnings if the economy weakens.

Spreads between those securities, which have a comparatively high default risk, and other corporate notes failed to narrow after Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s dovish comments last week, a sign that bondholders remain wary of risk.

A reckoning will arrive at some point, and with it “dramatic repricings,” because the credit market overall is skewed more than ever toward lower quality issuers, JPMorgan Asset Management’s Oksana Aronov said this month on Bloomberg Television.

“Are there companies that should not have made it past 2020 and won’t now that the Fed is not supporting them?” she said.