In the last week, the Small Business Administration has released a flurry of guidance — or what passes as guidance in this situation — governing the forgiveness of Paycheck Protection Program loans, culminating this morning in the release of a new Form 3508 for borrowers to use in requesting said forgiveness. Piecemeal as the guidance has been, with the issuance of the revised application, enough information is available for borrowers to build a solid understanding of how the SBA intends to merge the rules found in the original CARES Act, subsequent SBA regulations, and the recently-enacted Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act of 2020 into one final authoritative package.

Let’s take a look. But first, a bit of background.

PPP Loans, In General

On March 27, 2020, President Trump signed into law the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Securities (CARES) Act, a $2.3 trillion relief package designed to help individuals and businesses weather the economic damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The headliner of the CARES Act was the creation of the PPP, a new loan program under Section 7(a) of the Small Business Act designed to put nearly $600 billion into the hands of small businesses for use in paying employee wages and other critical expenses over the coming weeks and months.

The reason over two million businesses rushed to the bank to grab a PPP loan, however, was not because they were eager to saddle their struggling enterprises with more debt. Rather, the idea is that these PPP loans are loans in name only; once a borrower receives the funds, the amount spent over the next 8 weeks on payroll, mortgage interest, rent and utilities is eligible to be completely forgiven.

By late May, however, many borrowers were nearing the end of their 8-week periods, only to find that a number of barriers continued to prevent them from reaching full employment, and thus, achieving full forgiveness of their PPP loans. As a result, on June 5, 2020, Congress passed the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act (the Flexibility Act) of 2020, which made several dramatic changes to the legislative text of the CARES Act:

- The “covered period” over which a borrower may accumulate forgivable costs was extended from eight weeks to 24 weeks, or until December 31, 2020, whichever comes first. Borrowers with loans taken out prior to June 5, 2020, however, may elect to continue to use an 8-week covered period. As we’ll see later, the tripling of the covered period has a dramatic impact on the amount of forgivable costs a borrower can accumulate.

- While the SBA has previously provided that no more than 25% of a borrower’s forgivable costs may be attributable to non-payroll costs, the Flexibility Act increases this amount to 40%.

- The CARES Act provided a safe harbor — discussed below — whereby a borrower that cut headcount or salary throughout 2020 would not experience a reduction in the forgiveness amount provided the headcount or salary were restored prior to June 30, 2020. The new law extends this period to December 31, 2020.

- In the event a borrower CAN’T replace its headcount before December 31, 2020, the Flexibility Act provides a new bailout: the new law provides that no reduction in forgiveness will be required due to reduced FTEs provided the borrower, in good faith, is able to document any of the below:

- There was an inability to rehire individuals who were employees of the eligible recipient on February 15th,

- There was an inability to hire similarly qualified employees for unfilled positions on or before December 31, 2020, or,

- There was an inability to return to the same level of business activity as such business was operating at before February 15th due to compliance with requirements established or guidance issued by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Occupational Safety and Health Administration during the period beginning on March 21 1, 2020, and ending December 31, 2020, related to the maintenance of standards for sanitation, social distancing, or any other worker or customer safety requirement related to COVID– 19. This is the BIG ONE. It basically provides that if the world is such that on December 31st, restaurants and bars, for example, are unable to fully open due to government orders, any loss in FTEs resulting from such restrictions should NOT be taken into account in computing a required reduction in the forgivable amount.

With the relevant legislation laid out, let’s take a look at the new application, and how it interprets the changes made by the Paycheck Protection Program Flexibility Act of 2020.

Applying for Loan Forgiveness

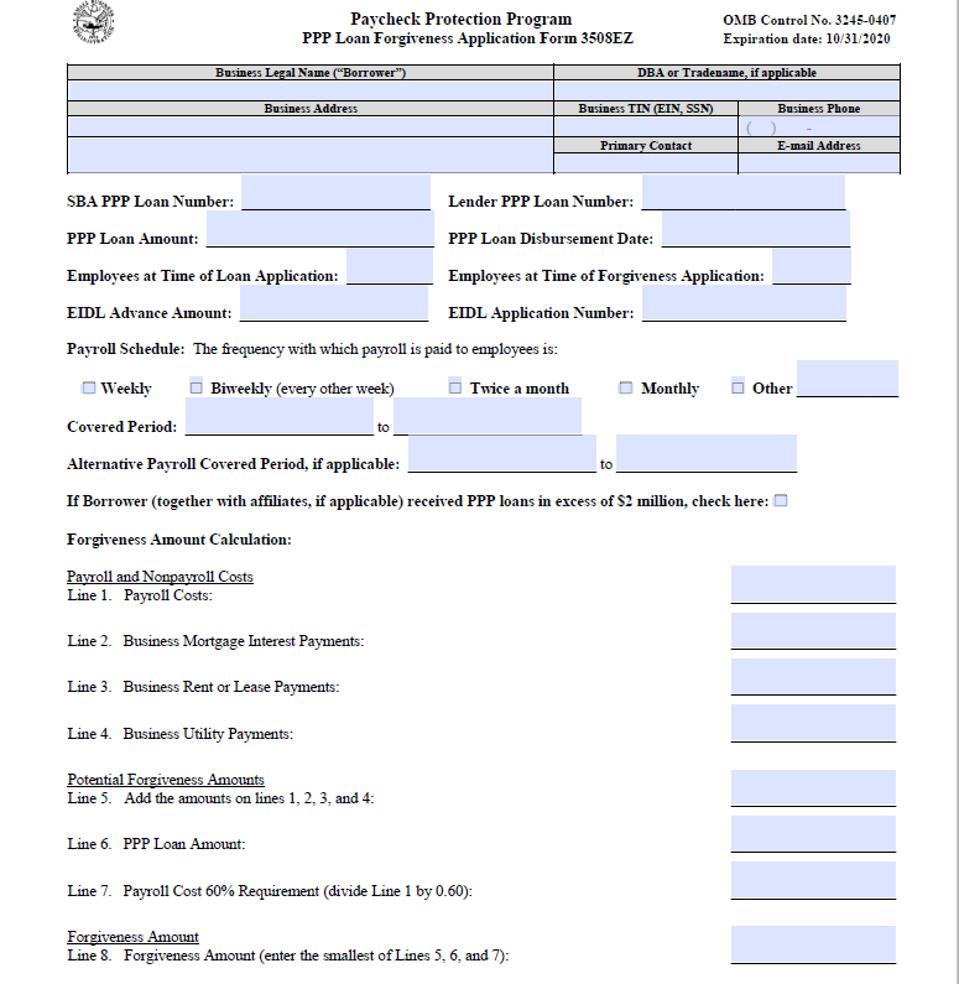

On Wednesday, the SBA updated Form 3508 as well as the relevant instructions. In addition, the SBA released a new, streamlined application for forgiveness in the form of Form 3508EZ, which may be used ONLY if certain requirements are met. We’ll address these requirements at the end of our discussion.

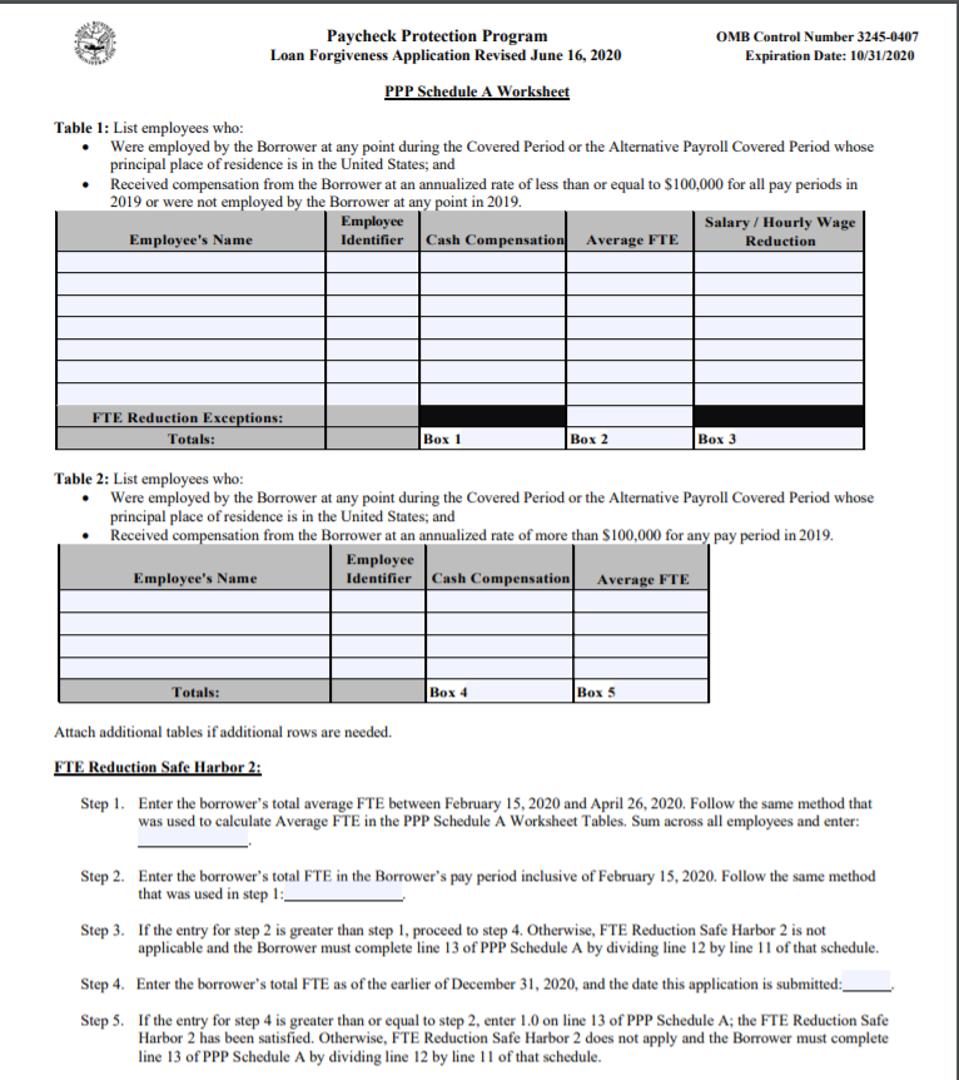

As was the case with the original application, there are two critical supporting schedules: Schedule A and the worksheet to Schedule A.

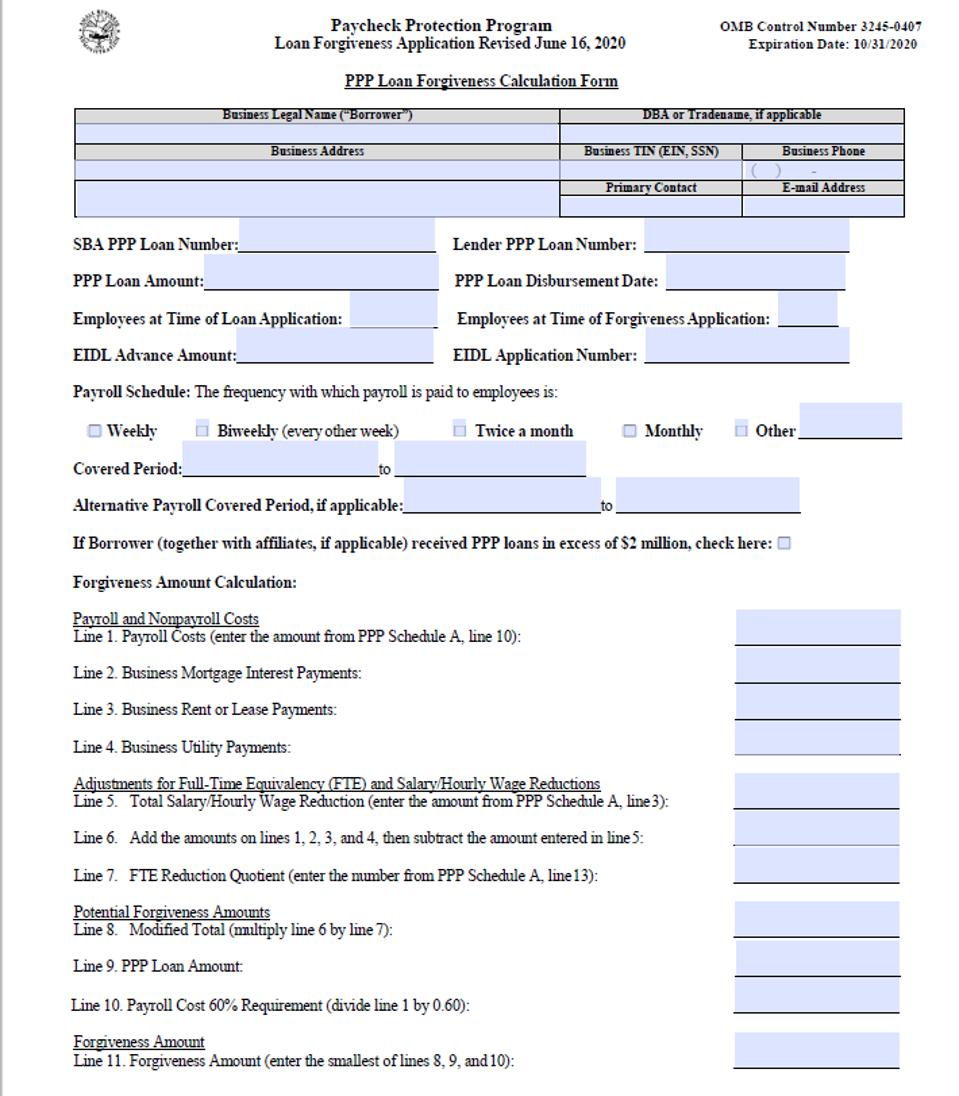

We will begin, however, with the application itself; specifically, the informational section that makes up the top half of the page. All instructions will be from the perspective of the borrower.

Top of Application Instructions

The application begins by asking you to provide your name, address and EIN, as well as SBA PPP loan number and lender PPP loan number. If you struggle with this part, it does not bode well for what’s to follow.

Next, you’re asked to provide a few items that may seem innocuous, but that may factor into the amount of your forgiveness:

PPP Loan Amount: This will serve as the maximum amount of loan eligible for forgiveness.

PPP Loan Disbursement Date: The date you receive the funds will generally signal the start of your period to accumulate expenses eligible for forgiveness, but as we’ll see, there is some flexibility in choosing the period specific to payroll costs.

Employees at Time of Loan Application: While this doesn’t appear to have any specific application to determining forgiveness, we will see that since you’re going to have to provide your number of employees for approximately 372 other periods, it can’t hurt to provide that detail for the date of the loan application as well.

Employees at Time of Forgiveness Application: As we’ll discuss below, the application states that to comply with the FTE reduction safe harbor, FTEs must be restored to February 15, 2020 levels by the EARLIER OF a) December 31, 2020, and b) the date the application is submitted.

Economic Injury Disaster Loan Advance Amount: These amounts were generally capped at $10,000, though later borrowers were often limited to $1,000 per employee, not to exceed a total of $10,000. As we’ll see later, when we arrive at Line 11 of the application – the maximum forgiveness amount – the SBA will reduce the amount forgiven by any EIDL advance that was received.

Economic Injury Disaster Loan Application Number: Any EIDL taken out after January 31, 2020, and used to cover payroll, was likely refinanced into your PPP loan. As a result, the SBA is looking to gather than information here.

Payroll Schedule: You must select the box that corresponds with your regular payroll schedule. This will help the SBA determine when payroll costs are paid or incurred and thus eligible for forgiveness. It will also drive the computation of full-time equivalent employees for several key periods, which will in turn be used to determine if a reduction in the amount eligible for forgiveness is required.

Covered Period: This is the first critical piece of information. The “covered period” can now be as many as FOUR different time frames. The default setting is that the covered period is the 24-week period beginning on the date you received the loan disbursement. Only the costs paid OR incurred within the 24-week period are generally eligible for forgiveness.

Specific rules govern the “paid and incurred” treatment of payroll costs. Payroll costs are paid on the day the paychecks are distributed or the borrower originates an ACH credit transaction. Thus, you could presumably receive PPP loans on April 26 and immediately pay – as part of your regular payroll process – wages that had been earned by the employees for the previous two weeks, and include the amounts in the forgiveness calculation because the amounts had been PAID within the covered period.

The application instructions further provide that payroll costs are incurred on the day they are earned, before providing additional flexibility by allowing the payroll costs incurred for your last pay period of the 24-week period to be eligible for forgiveness as long as they are paid no later than the next regular payroll date.

For non-payroll costs such as mortgage interest, rent and utilities, to qualify for forgiveness, these expenses must either be: 1) paid DURING the 24-week covered period, or 2) incurred during the 24-week period, and paid by its next regular due date, even if that due date is outside the 24-week period.

Once again, it would appear that by allowing all payments made DURING the period to be eligible for forgiveness, borrowers are permitted to pay rent, interest, or utilities related to periods prior to the 24-week period and have those expenses forgiven.

IMPORTANT: If you received your loan prior to June 5, 2020 — the passage of the PPP Flexibility Act — you may elect to use the 8-week covered period provided by the CARES Act. Presumably, you would only do this if you 1) spent all of your PPP loan on eligible costs within the 8-week window, 2) did not reduce any salary or headcount during the 8-week period, and 3) are eager to move on from the PPP process and never speak of it again.

Alternative Payroll Covered Period, if applicable: The instructions to the application allow for flexibility in choosing your covered period specific to payroll costs. You are permitted to choose an “alternative payroll covered period,” which is the 24-week (168 day) period beginning on the first day of the first pay period following the disbursement date, allowing a business to neatly align its covered period with the beginning of a pay period. Thus, if you received your PPP loan on April 20, 2020, and the first day of your next pay period is April 26, 2020, you may elect to count the payroll costs — and only the payroll costs — for the 24-week period beginning April 26, 2020, rather than the 24-week period beginning April 20, 2020.

Obviously, if you elect to use the 8-week covered period, you simply adjust the language above to suit a 56-day period rather than a 168-day period.

If Borrower (together with affiliates, if applicable) received PPP loans in excess of $2 million, check the box: Uh…if your loan was less than $2 million, you’re going to want to remember to NOT. CHECK. THIS. BOX. The SBA announced what is effectively – and perhaps literally — a get-out-of-jail free card by providing a safe harbor for those borrowers who received less than $2 million in PPP funds. These borrowers will be treated as having made the required certification that the loan was necessary in good faith, and thus won’t be subject to the same additional scrutiny from the SBA that borrowers of loan amounts in excess of $2 million will face.

With the informational items out of the way, it’s time to turn our attention to the actual calculation, beginning with Line 1 of the application:

Line 1: Payroll Costs (Enter the amount from PPP Schedule A, Line 10).

As you’ll see, Line 1 directs us to Line 10 of Schedule A, which we can’t compute until we’ve determined items on the Worksheet for Schedule A. As a result, we’re going to start on the ground floor, with the Worksheet for Schedule A, and then build our way back up to the application.

Worksheet to Schedule A

The Worksheet to Schedule A has not changed from its previous iteration, and looks like so:

The worksheet allows us to perform five critical computations:

- Most importantly, it is here where we will compute eligible compensation for each employee,

- We will make sure to cap the compensation of employees at $100,000 on an annualized basis,

- In addition, we will determine the number of full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) for the covered period (or alternative payroll period, if elected),

- We will determine if forgiveness must be reduced due to a reduction in the salary of certain employees, and

- We will use the FTEs determined in #3 above to determine if a reduction in the amount eligible for forgiveness is required because FTEs were reduced during the covered period.

Let’s get started. We begin by identifying each employee, but we do NOT include:

- Independent contractors,

- Owner-employees,

- Self-employed individuals, or

- Partners.

For self-employed individuals with no employees, the forgiveness related to payroll costs is both purely mechanical and mathematically assured. This is because the loan proceeds were calculated by taking 2.5/12 of the borrower’s 2019 Form Schedule C net profit, and in turn, the forgivable payroll costs for a self-employed taxpayer — or what is referred to as “owner replacement cost” — is ALSO calculated by taking 2.5/12 of the borrower’s 2019 Form Schedule C net profit. Thus, a self-employed taxpayer who had $100,000 of Schedule C net profit in 2019 would have borrowed $20,833 (2.5/12 of $100,000), and will have forgiven $20,833 (2.5/12 of $100,000).

As for payments to owner-employees and partners, we’ll see these amounts are pulled – subject to significant limitation – into Schedule A and included as costs eligible for forgiveness.

Employees are segregated into two tables:

Table 1 is for those with annualized compensation for ALL pay periods in 2019 of less than $100,000. The reason these employees are isolated is because as we’ll see, if their salaries are reduced during the covered period, a reduction in the amount eligible for forgiveness may be required. What is not clear is how strict the “any pay period” limits are applied: what if an employer was paid a salary of $80,000 in 2019, but received a bonus of $5,000 during one two-week pay period. Isn’t the annualized salary for that two week period in excess of $100,000, even though the employee only received total compensation of $85,000?

Table 2 is reserved for those taxpayers with annual compensation in excess of $100,000 during 2019. These employees are isolated because if a borrower were to slash THESE salaries, no reduction in forgiveness is required.

Now that we understand the difference between the tables, let’s fill them out:

Table 1

Cash Compensation

The CARES Act provides that the amounts spent on “payroll costs” during the 24-week covered period are eligible for forgiveness. Including in payroll costs are certain compensation amounts; specifically, the sum of payments of any compensation with respect to employees that is a:

- Salary, wage, commission, or similar compensation;

- Payment of cash tip or equivalent;

- Payment for vacation, parental, family, medical, or sick leave; or

- Allowance for dismissal or separation.

Compensation does not include, however:

- The compensation of an individual employee in excess of an annual salary of $100,000, as prorated for the covered period. As a result, in no situation should you enter more than $46,154 (24/52 * $100,000) in this column for either Table 1 or Table 2. Alternatively, if you elect to use the 8-week covered period, the compensation paid to any one employee that is eligible for forgiveness cannot exceed $15,384 (8/52 * $100,000).

- Any compensation of an employee whose principal place of residence is outside of the United States;

- Qualified sick leave wages for which a credit is allowed under section 7001 of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (Public Law 116–127); or

- Qualified family leave wages for which a credit is allowed under section 7003 of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (Public Law 116–127).

Here’s where the advantage of the PPP Flexibility Act becomes obvious: PPP loans were made based on 2.5 months of the borrower’s average monthly payroll costs for 2019. Now, borrowers will get 24 weeks —or nearly six months — to incur forgivable payroll costs. Thus, for many borrowers, the total “forgivable” costs will far exceed the loan proceeds; as a result, even if the borrower finds itself subject to a reduction in the forgivable amount because of reduced salary or headcount, the math is such that even AFTER the reduction, the forgivable costs will exceed the principal balance of the loan.

Average FTE:

To determine the average full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) for the 24-week covered period (or the 8-week or alternative payroll covered period, if elected), for each qualifying employee, determine the average number of hours worked per week and divide by 40, before rounding to the nearest tenth. The maximum amount for each employee is 1.0. Alternatively, you can skip the math and use 1.0 for every employee who worked 40 hours per week and 0.5 for every employee who didn’t meet that standard. Either way you get there, you will ultimately arrive at the average FTE throughout the relevant covered period.

Example. X Co. borrowed a $100,000 PPP loan on April 10, 2020. X Co. incurred $100,000 of costs eligible for forgiveness over the next 24 weeks.

For the 8-week period beginning April 20, X Co. had the following employees:

- A, who averaged 45 hours per week during the period,

- B, who averaged 40 hours per week during the period,

- C, who averaged 28 hours per week, and

- D and E, who averaged 20 hours per week.

For the 8-week covered period, X Co. had 3.7 FTEs:

- A: 45/40 capped at 1.0

- B: 40/40 = 1.0

- C: 28/40 = .7

- D &E: 20/40 = .5 each

If X Co. chose instead to use the simplified method, it would have 3.5 FTEs:

- A: 45/40 capped at 1.0

- B: 40/40 = 1.0

- C: 28/40 = .5

- D &E: 20/40 = .5 each

While a 24-week covered period is certainly more advantageous than an 8-week period, it’s not without its downside. For example, a borrower will now have to gather information necessary to compute FTEs for a period three times longer than previously required. As we’ll see below, the same holds true for the salary reduction rules.

It is important to note that the application now states the FTE hours are based on hours PAID, rather than worked. Thus, a once-full-time employee who was being paid in full while on furlough or working reduced hours would presumably continue to count as a full FTE.

Salary/Hourly Wage Reduction

Here’s where things go off the rails a bit. The total amount of loan forgiveness will eventually be reduced by the amount of any reduction in total ANNUAL salary or AVERAGE wages of any employee during the covered 24-week period (or 8-week period, if you so choose), who did not receive, during any single pay period during 2019, wages or salary at an annualized rate of pay of more than $100,000. The reduction in forgiveness amount is required if the reduction in wages over the 24-week period is in excess of 25% of the total salary or wages of the employee during the period from January 1, 2020 through March 31, 2020. Again, this is why employees with annualized salary of less than $100,000 are isolated in Table 1; by definition, only these employees can experience a reduction in salary during the covered period that necessitates a corresponding reduction in the amount eligible for forgiveness.

To determine the amount of reduction required, you must go through the following steps for EACH employee:

- Step 1: Determine the average annual salary or hourly wage for each employee during the covered period (or alternative payroll period, if elected).

- Step 2: Determine the average annual salary or hourly wage for each employee during the period from January 1, 2020, through March 31, 2020.

- Step 3: Divide Step 1 by Step 2.

- Step 4: If Step 3 is greater than 75%, no reduction is required. Do not fill out the column in Table 1 for this employee.

- Step 5: If Step 3 is LESS than 75%, a reduction is required, but as we’ll see shortly, the reduction may be reinstated. The reduction is tentatively determined by multiplying the amount determined in Step 2 by 75%, and then subtracting from that result the amount from Step 1. For a salaried employee, take this result and multiply it by 24 (or 8 if using an 8-week covered period). Then divide the amount by 52. This is the amount of the required reduction.

- For an hourly worker, the amount of the reduction is determined by first multiplying the average number of hours worked per week from January 1, 2020, through March 31, 2020, by the amount determined by subtracting the amount determined in Step 1 from 75% of the amount determined in Step 2. The result is then multiplied by 24 (or 8 if using an 8-week period) to arrive at the total reduction in forgiveness.

You’re lost, aren’t you? Let’s do an example.

Example. Employee A was paid an annual salary of less than $100,000 for 2019. A was paid $24,000 during the 24-week covered period. A was paid $20,000 for the period January 1, 2020, through March 31, 2020.

- Step 1: A’s average annual salary was $52,000 for the 24-week covered period ($24,000/24*52).

- Step 2: A’s average annual salary was $80,000 for the period January 1, 2020, through March 31, 2020 ($20,000 *4).

- Step 3: $52,000/$80,000 = 65%.

- Step 4: n/a

- Step 5: Before application of the safe harbor, A’s employer would reduce forgiveness attributable to A by the following amount: $80,000 * 75% = $60,000. $60,000 – $52,000 = $8,000. $8,000/52*24 = $3,690.

[Here’s another downside of the 24-week period. A longer covered period means a greater reduction in forgiveness if an employees salary or hourly rate are reduced during that time. After all, you’re multiplying the average salary or hourly rate reduction by 24 instead of 8.

The reduction is not required, however, if a safe harbor is met. Whether the safe harbor is met is determined via the following steps:

- Step 1: Determine the employee’s annual salary or hourly wage as of February 15, 2020.

- Step 2: Determine the average annual salary or hourly wage for the period from February 15, 2020 through April 26, 2020.

- Step 3: If Step 2 is greater than Step 1, the safe harbor does not apply. Compute the reduction in forgiveness as determined in Step 5, above. If Step 2 is less than Step 1, proceed to Step 4.

- Step 4: Determine the average annual salary or hourly wage for the employee as of the EARLIER OF a) the date the application is submitted, and b) December 31, 2020. If that amount is equal to or greater than Step 1, the safe harbor has been met. In other words, the SBA will ignore a reduction in salary during the covered period relative to the 1st quarter of 2020, but ONLY IF that salary is restored to what it was on February 15, 2020, by the earlier of a) the date of the application, or b) the end of 2020.

This is the first time we’ve seen the date of the application be relevant in determining the restoration of salary. This would appear to mean that a borrower who cut an employee’s salary in April and restored it in July, but then cut it again before applying for forgiveness in August, would not satisfy the safe harbor, even though the salary HAD BEEN, at least temporarily, restored prior to December 31, 2020.

Example. Continuing the previous example, assume that on February 15, 2020, A was being paid an annual salary of $75,000. After the arrival of COVID-19, however, A’s average salary for the period February 15, 2020 through April 26, 2020, was reduced to $55,000. It was further reduced for much of May, which is what resulted in A being paid only $24,000 for the covered period. By December 1, 2020, however, A’s annual salary was increased to $75,000. Even though A’s salary has returned only to the amount he was paid on February 15 ($75,000) and not the amount he was paid throughout the first quarter ($80,000), the safe harbor is met and no reduction is required.

If the safe harbor had NOT been met, A’s employer would enter $3,690 in the “Salary/Hourly Wage Reduction” column in Table 1.

Table 2

In Table 2 we’ll report those employees who earned more than $100,000 on an annualized basis in 2019. If the salary of these employees is cut during the covered period, no reduction results.

FTE Reduction Safe Harbor

The amount of loan forgiveness may ALSO be reduced if the borrower reduces headcount during the covered period. Just as we saw with the reduction resulting from reduced salary, however, the reduction may be ignored if a safe harbor is satisfied.

Your forgiveness is reduced if your average number of full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) during the covered period is less than the average number of FTEs for any of the following periods, at your election:

- The period beginning on February 15, 2019 and ending on June 30, 2019; o

- The period beginning on January 1, 2020 and ending on February 29, 2020, or

- For a seasonal employer, as determined by the SBA, either of the two previous periods or any 12-week period between May 1, 2019 and September 15, 2019.

As you’ll remember, we determined FTEs above in the instructions to Table 1. But just to reinforce the concept, let’s build out this example again.

Example. X Co. borrowed a $100,000 PPP loan on April 10, 2020. X Co. incurred $100,000 of costs eligible for forgiveness over the next 24 weeks.

For the 24-week period beginning April 20, 2020, X Co. had the following employees:

- A, who averaged 45 hours per week during the period,

- B, who averaged 40 hours per week during the period,

- C, who averaged 28 hours per week, and

- D and E, who averaged 20 hours per week.

For the 24-week covered period, X Co. had 3.7 FTEs:

- A: 45/40 capped at 1.0

- B: 40/40 = 1.0

- C: 28/40 = .7

- D &E: 20/40 = .5 each

Using the simplified method, X Co. would have only 3.5 FTEs, so doing the math benefits X Co. by resulting in a larger number.

Assume further that for the periods February 15, 2019 through June 30, 2019, and January 1, 2020 through February 29, 2020, X Co. had the following employees:

- A, who averaged 45 hours per week during the period,

- B, who averaged 40 hours per week during the period,

- C, who averaged 40 hours per week,

- D and E, who averaged 28 hours per week, and

- F and G, who averaged 40 hours per week.

For those 8-week periods, X Co. had 6.4 FTEs:

- A: 45/40 capped at 1.0

- B: 40/40 = 1.0

- C: 40/40 = 1.0

- D &E: 28/40 = .7 each

- F & G: 40/40 = 1 each

Thus, before considering any safe harbor or reinstatement, X Co.’s amount eligible for forgiveness of $100,000 must be reduced by multiplying $100,000 by 3.7/6.4. Thus, the forgiveness is tentatively capped at $57,813.

A borrower may ignore the required reduction, however, if one of several safe harbors are met.

For the first safe harbor, the borrower must first use the methodology described above to determine FTEs for two additional periods:

- The period from February 15, 2020, through April 26, 2020, and

- For the pay period that includes February 15, 2020,

If the average FTEs for the first period is less than the FTEs for the second period, the borrower must then compare the average FTEs for the second period to the total FTEs as of the EARLIER OF a) December 31, 2o20, or b) the date the application is submitted. If the FTEs on the earlier of those two dates are greater than the FTEs on February 15, 2020, the safe harbor is met and no reduction is required.

Example. Continuing the example above, assume X Co. had 4.2 FTEs for the period February 15, 2020, through April 26, 2020, and 4.5 FTEs on February 15, 2020. X Co. then reduced the hours of some of their employees and terminated others, resulting in only 3.7 FTEs for the covered period. Because X Co. had more employees on February 15, 2020, then during the period February 15, 2020, through April 26, 2020, X Co. must then compare the number of FTEs on February 15, 2020 – 4.5 – to the number on the earlier of a) December 31, 2020, or 2) the date the application is submitted. Provided the number of FTEs on that date is equal to or greater than 4.5, no reduction in forgiveness is required.

There are additional safe harbors as well. If an employer can show that it made a good-faith, written offer to rehire an employee during the covered period but was rejected by the employee, then that reduction in headcount will not result in a reduction in forgiveness. The same is true if an employee was fired for cause, voluntarily resigned, or voluntarily required and receive a reduction in hours. These reductions in FTEs are actually added back on Table 1 of the worksheet to Schedule A. What is not clear is exactly what amount you’re adding back: is it the FTE the employee was at the time they left service? Some previous time?

Finally, the PPP Flexibility Act added an additional safe harbor. No reduction in forgivable costs related to FTE reduction is required if the borrower, in good faith, is able to document that it was unable to operate between February 15, 2020, and the end of the Covered Period at the same level of business activity as before February 15, 2020, due to compliance with requirements established or guidance issued between March 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020, by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, related to the maintenance of standards for sanitation, social distancing, or any other worker or customer safety requirement related to COVID-19. 2.

With that, we have finished completing the Worksheet to Schedule A, and can now turn our attention to Schedule A itself.

Schedule A

Schedule A looks like this:

Information from Schedule A is used to populate several lines on the forgiveness application. Let’s take Schedule A line-by-line.

Line 1: Enter Cash Compensation (Box 1) from PPP Schedule A Worksheet, Table 1: Self-explanatory. Take the total amounts you entered on this column of Table 1, but only Table 1 (at this point).

Line 2: Enter Average FTE (Box 2) from PPP Schedule A Worksheet, Table 2: Also self-explanatory. Drop in the total FTEs for the covered period from Table 1.

Line 3: Enter Salary/Hourly Wage Reduction (Box 3) from PPP Schedule A Worksheet, Table 1: You get the idea. Take the total from this column in Table 1 and drop it onto Line 3.

Line 4: Enter Cash Compensation (Box 4) from PPP Schedule A Worksheet, Table 2: Same concept plays out now for Table 2. Enter the total cash compensation paid. And remember, it cannot exceed $46,152 for any one employee.

Line 5: Enter Average FTE (Box 5) from PPP Schedule A Worksheet, Table 2: Drop in the FTEs you computed in Table 2.

Lines 6 – 8: Non-Cash Compensation Payroll Costs During the Covered Period or Alternative Payroll Covered Period

First, some background. In addition to cash compensation, “payroll costs” include:

- Payment required for the provisions of group health care benefits, including insurance premiums;

- Payment of any retirement benefit; or

- Payment of State or local tax assessed on the compensation of employees.

Schedule A asks us to put the first item on Line 6, the second on Line 7, and the third on Line 8. For employees with no ownership interest, these amounts are in ADDITION TO the annualized compensation cap of $100,000. Thus, an employee could have up to $46,152 of compensation from Table 1 or 2 included on Schedule A, as well as amounts allocable to that employee reflecting his or her share of health costs, retirement benefits, or state and local taxes on Lines 6-8.

Specific to Line 6, we do NOT include employer health insurance contributions made on behalf of a self-employed individual, general partner, or owner-employee of an S-corporation, because such payments are already included in their compensation. It appears that retirement plan contributions for an owner-employee would be included on Line 7, in addition to the maximum payroll cost for the owner-employee as discussed in Line 9.

This last bit of news is new on the latest application, and it’s IMPORTANT, though perhaps not for the reason you think. Yes, it says we don’t get to add health costs attributable to an owner, but more importantly, for the FIRST TIME, it makes clear that when the SBA is referencing an “owner-employee,” it includes the shareholder of an S corporation. This matters greatly when we get to Line 9.

It’s also worth nothing that there is no reason to believe that “owner-employees” do not include shareholders of a C corporation. The application singles out S corporation shareholders because pursuant to Revenue Procedure 91-26, these taxpayers must include health-insurance paid on their behalf as compensation; C corporation shareholders do not.

Line 9: Total amount paid to owner-employees/self-employed individual/general partners: This is where we finally include payroll costs for self-employed taxpayers, general partners and the aforementioned “owner-employees” of S and C corporations.

As discussed previously, the forgiveness for a self-employed taxpayer will be mechanical: 2.5 months of the taxpayer’s 2019 Schedule C , Line 31 (capped at $100,000). No further limitation applies.

For general partners and owner-employees of a C or S corporation, there are two limitations that apply. First, the maximum cost for 2020 is capped at 2.5 months of an annualized $100,000 salary, or $20,833 (or $15,384 for a borrower using the 8-week covered period). Compare this to the $46,152 an employee can be paid throughout the covered period. Then, the forgivable amount is further limited to 2.5 months of the 2019 compensation of the general partner or owner-employee. This would prevent an owner from increasing their compensation during the covered period to maximize forgiveness by limiting the amount included in the forgivable amount to 10/52 of the owner’s compensation for 2019.

Line 10: Payroll costs (add lines 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9): Do as they say.

Line 11: Average FTE during the Borrower’s chosen reference period: Let’s assume we DON’T satisfy any of the safe harbors discussed above for FTE restoration. In that case, we’re going to have to compute the reduction in forgiveness. As a result, the SBA wants to know our FTEs for the relevant base period we chose. Pick your base period, compute your FTEs, and provide the numbers here.

Line 12: Total Average FTE (add lines 2 and 5): Again, we’re doing this to compute the reduction in forgiveness when headcount is cut and not replaced. The formula is to divide the FTEs for the covered period by the number in Line 11, and so on this line we enter the FTEs for the covered period.

Line 13: FTE Reduction Quotient: On this line, we simply divide Line 12 by Line 11 to arrive at the reduction quotient. If the safe harbor is met, this amount should be 1.0, and no reduction is required.

Ok, now, were going to take much of what we did on Schedule A and move it to the application. The application will require some new information as well, however. Let’s take a look:

Application for Forgiveness

Here she is:

Five thousand words ago, we covered the informational top half of the application for forgiveness. Now we jump back into the application, picking up on Line 1.

Line 1: Payroll Costs: This work has been done. Simply drop in the amount from Schedule A, Line 10, which summarizes the compensation, health care costs, retirement benefits, and state taxes for each eligible employee.

Line 2: Business Mortgage Interest Payments: As a reminder, in addition to payroll costs, the CARES Act permits forgiveness for three other classes of expenses paid during the covered period.

- Any payment of interest on any covered mortgage obligation (not including any prepayment of or payment of principal on a covered mortgage obligation). The term “covered mortgage obligation” means any indebtedness or debt instrument incurred in the ordinary course of business that is a liability of the borrower, is a mortgage on real or personal property, and was incurred before February 15, 2020,

- Any payment on any covered rent obligation. The term “covered rent obligation” means rent obligated under a leasing agreement in force before February 15, 2020,

- Any covered utility payment. The term “covered utility payment” means payment for a service for the distribution of electricity, gas, water, transportation, telephone, or internet access for which service began before February 15, 2020.

As we discussed in our “paid or incurred” section, it appears mortgage interest owed in arrears can be paid during the covered period and be forgiven, and mortgage interest incurred DURING the covered period but paid before or on the next scheduled due date will also be forgivable, even if that date is after the end of the covered period.

Enter the amount of mortgage interest “paid or incurred” during the covered period on Line 2.

Line 3: Business Rent or Lease Payments: Enter the amount of business rent or lease payments paid or incurred during the covered period on Line 3. The same rules used for mortgage interest expense apply in determining whether the expenses are paid or incurred during the covered period.

Line 4: Business Utility Payments: Enter the amount of utility payments paid or incurred during the covered period on Line 3. The same rules used for mortgage interest expense apply in determining whether the expenses are paid or incurred during the covered period.

Borrowers continue to clamor for more guidance as to what can be included in these three buckets, but I’m not sure its coming. As we’ll see shortly, the SBA has a more effective way of safeguarding against a borrower using the bulk of their loan proceeds on non-payroll costs: the cap on forgivable non-payroll costs of 40% of the total forgivable amount.

Line 5: Total Salary/Hourly Wage Reduction: Lines 1-4 compute the TOTAL amount eligible for forgiveness. As we’ve learned, however, this amount is reduced if salaries are cut (as determined in Table 1 of the Worksheet to Schedule A) or FTEs are reduced (as determined at the bottom of the worksheet to Schedule A). Here, any amount attributable to a reduction in salaries as reported on Table 1 are reported on Line 5, reducing the total amount eligible for forgiveness.

Line 6: On this line, we simply net the reduction on Line 5 with the sum of costs eligible for forgiveness on Lines 1-4 to arrive at the maximum amount eligible to be forgiven.

Line 7: FTE Reduction Quotient: One Line 13 of Schedule A, when the safe harbor for reduction in headcount was not satisfied, we divided our FTEs for the covered period by the FTEs for the base period to arrive at the quotient that must be multiplied by the maximum amount eligible for forgiveness to determine the required reduction. That quotient from Line 13 is inserted onto Line 7 of the application.

Line 8: Modified Total: In Lines 8-10, we will determine the forgiveness amount. It is the LESSER of three amounts:

1. Line 8: The net amount from Line 6 (total costs less salary reduction amount) multiplied by the quotient on Line 7 for headcount reduction,

2. Line 9: the principal balance of the loan, and

3. Line 10: The payroll costs (Line 1 of the application) divided by 60%. This line ensures that no more than 40% of the total forgiveness is attributable to non-payroll costs.

Line 9: PPP Loan Amount: Enter the PPP loan amount.

Line 10: Payroll Cost 60% Requirement: Here, divide the total payroll costs from Line 1 by 60%.

Line 11: Forgiveness Amount: We’ve done it! The lesser of Lines 8, 9, and 10 is your forgiveness amount.

If you’ve stuck with me this long, you’re exactly the type of glutton for punishment who would like nothing more than to take EVERYTHING we just did and work through a real-life example. Let’s do it.

CASE STUDY

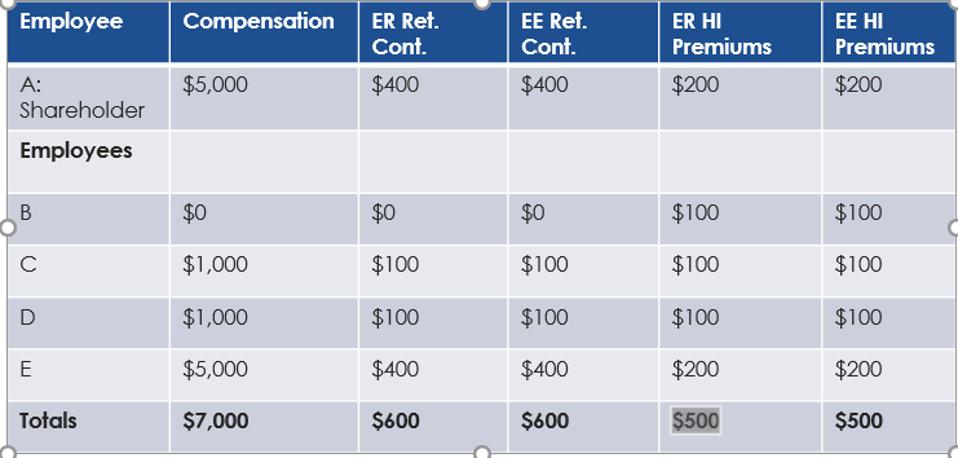

During 2019, X Co. had 5 employees. A is the sole shareholder of X Co. The total costs X Co. incurred for all payroll costs were as follows:

- A, B, and E worked 40 hours a week.

- C worked 30 hours a week.

- D worked 20 hours a week.

From January 1, 2020 – March 31, 2020, X Co. incurred the following payroll costs:

- A, B and E worked 40 hours a week.

- C only worked 20 hours a week during Q1.

- D worked 20 hours a week.

Beginning April 1: B is furloughed and is not paid, though X Co. does pay B’s health care costs during the furlough period. C requests her hours to be cut in half; pay is cut in half as well. D’s pay is cut in half, but hours remain the same.

- X Co. uses biweekly pay periods. Payment is made the Friday after the pay period ends.

- On April 25th, X Co. receives a PPP loan of $70,000. X Co.’s next pay period begins on May 1st.; payment for the period April 15 – April 30 is made on May 1st.

- X Co. elects to use the alternative covered payroll period.

- By December 31, 2020, B is not brought back. C continues to have reduced hours.

- Over the next 24 weeks, X Co. pays $40,000 of rent and $10,000 of utilities.

X Co. turns first to the application, and fills out the relevant information on the top half of the form.

Loan Amount: $70,000

Loan Disbursement Date: April 25th, 2020

Employees at Time of Loan Application: 5

Employees at Time of Forgiveness Application: 5

EIDL Information: X Co. did not take out an EIDL, so these two sections are inapplicable.

Payroll Schedule: Twice a month.

Covered Period: 24 weeks: April 25 – October 16, 2020.

During the 24-week covered period, X Co. makes the following payments:

In addition, on May 1, X Co. made the following payments for the previous payroll:

Now, we have to jump to the Worksheet for Schedule A, and start computing compensation costs and possible reductions in the amounts eligible for forgiveness.

Worksheet A

We start by completing Table 1:

A few things to note:

- A and E are not included in Table 1 because A is an owner-employee and E earned more than $100,000 in 2019.

- D was paid $10,000 during Q1 of 2020, which annualizes to $40,000. D was paid only $15,000 during the 24-week period, which annualizes to $32,500. D took a pay cut, but not in excess of 75% of his base period salary. Thus, no reduction in forgiveness is required.

- In addition, while C has gone from half-time to quarter-time, C voluntarily requested the reduction; thus, the drop in FTE by .25 is not required, and instead “added back” on the FTE reduction exemption line. The same would be true if C were fired for cause or quit.

Next, we populate Table 2, for employee E. In total, it looks like this:

Next, we must determine if any reduction is required due to headcount.

Reduction in Forgiveness Due to FTEs

As determined in Tables 1 and 2, X Co. had 2 FTEs during the covered period. X Co. must compare these FTEs to the 3 FTEs X Co. had during the possible base periods.

Thus, X Co. had a reduction in FTEs during the covered period relative to the base period. As a result, we tentatively have a reduction quotient of 2/3.

This quotient, however, will be eliminated if any of the safe harbors are met. We know B was not rehired before December 31, 2020, so that option is out. Assume further that B’s return was not precluded by COVID-19 restrictions that kept X Co. from operating at full capacity. As a result, there is an FTE reduction quotient of 67%.

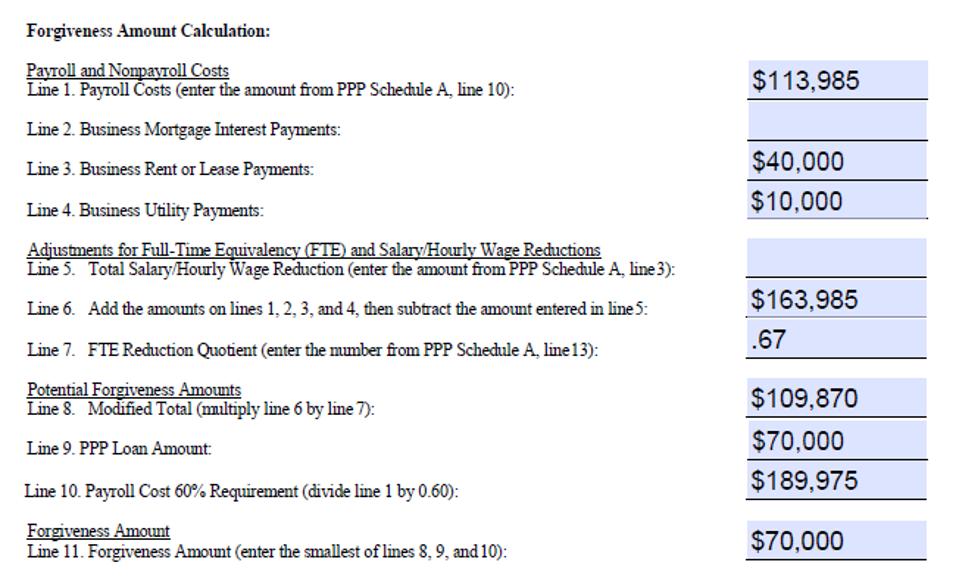

Next, we flip over to Schedule A:

Schedule A:

You’ll note that the amounts for Line 6 and 7 come from the table above where all payroll costs for the 24-week period were detailed (I just made up Line 8). We did not include health insurance costs paid to A, the owner-employer, because these costs are not forgivable. We did, however, include the retirement contributions paid on A’s behalf. And of course, we did not include ANY employee contributions to either health insurance or retirement plan contributions. We also capped A’s salary at the lesser of $20,833 for 2020, or 10/52 of the 2019 compensation.

Now that Schedule A has been filled out, we can head over to the application and finish this thing off:

In this case, the full loan was forgiven, even though FTEs were reduced by 33%. Why? Simple: X Co. borrowed only $70,000 — based on 2.5 months of average monthly payroll for 2019 — but then had 24 weeks to spend $113,000 in payroll costs in 2020. Add on the rent and utilities, and even with a 33% haircut the full loan is forgiven.

Hopefully this analysis helps. I’m sure a bit more guidance is coming, but I’d be surprised if its anything that really moves the needle. As the case study illustrates, the move to a 24-week covered period greatly increases the chances a borrower will accumulate enough costs to achieve full forgiveness, even in the event that FTEs can’t be retained and none of the safe harbors are available. And of course, it full forgiveness for a self-employed taxpayer with no employees is now guaranteed.

Finally, in addition to the revised Form 3508, the SBA issued a new, streamlined Form 3508EZ that can be used only if at least one of the following three requirements are met:

- The borrower is a self-employed individual, independent contractor, or sole proprietor who had no employees at the time of the PPP loan application and did not include any employee salaries in the computation of average monthly payroll in the Borrower Application Form (SBA Form 2483).

- The Borrower did not reduce annual salary or hourly wages of any employee by more than 25% during the Covered Period or the Alternative Payroll Covered Period (as defined below) compared to the period between January 1, 2020 and March 31, 2020 AND The Borrower did not reduce the number of employees or the average paid hours of employees between January 1, 2020 and the end of the Covered Period. (Ignore reductions that arose from an inability to rehire individuals who were employees on February 15, 2020 if the Borrower was unable to hire similarly qualified employees for unfilled positions on or before December 31, 2020. Also ignore reductions in an employee’s hours that the Borrower offered to restore and the employee refused. See 85 FR 33004, 33007 (June 1, 2020) for more details, or

- The Borrower did not reduce annual salary or hourly wages of any employee by more than 25% during the Covered Period or the Alternative Payroll Covered Period (as defined below) compared to the period between January 1, 2020 and March 31, 2020 AND The Borrower was unable to operate during the Covered Period at the same level of business activity as before February 15, 2020, due to compliance with requirements established or guidance issued between March 1, 2020 and December 31, 2020 by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, related to the maintenance of standards of sanitation, social distancing, or any other work or customer safety requirement related to COVID-19.

If one of these requirements are meant, it simply means that reduction in forgiveness for FTE or salary reductions are not required, and thus some of the ancillary computations on the full Form 3508 are superfluous. As a result, the Form 3508EZ looks like so:

It’s taken a long, strange road to get here, but it appears to have been worth the wait, because far more borrowers should now be able to fully walk away from their PPP loans.

Now, if we could just get the IRS to allow borrowers to DEDUCT the amounts spent with those funds…