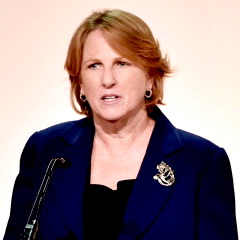

National Taxpayer Advocate (NTA) Erin Collins formally directed the IRS to take immediate steps toward implementing existing scanning technology to process tax returns filed on paper.

Collins issued the directive, which is dated March 29, under her authority pursuant to a delegation order in the Internal Revenue Manual to mandate administrative or procedural changes by the IRS to improve its functional operation or grant relief to taxpayers to protect their rights or to provide them an essential service.

In an NTA blog post on the Taxpayer Advocate Service website, Collins said the directive was necessitated by repeated warnings that processing paper returns remain a weakness for the IRS. As she said in her 2021 Annual Report to Congress in January, “paper is the IRS’s Kryptonite, and the IRS is buried in it.”

She cited recent updates on paper return processing that suggest the problem is not getting better: As of March 18, the paper return backlog numbered nearly 15 million returns, Collins said. Representing processing delays of 10 months or more, the backlog includes 4.7 million original individual income tax returns, 2.6 million amended individual income tax returns, 4.9 million original business tax returns, and 1.2 million amended business tax returns.

“Over the past year, the IRS has not made progress in reducing its backlog,” Collins said in the directive, noting that as of a year earlier, unprocessed original individual returns numbered slightly fewer, 4.6 million.

If the IRS is to meet its stated goal of eliminating its backlog by the end of 2022, it will need to adopt new ways of processing paper returns, mostly by implementing scanning technology that itself is hardly new, Collins said.

“If the IRS had implemented scanning technology, it is unlikely the current processing backlog would exist,” she said.

Moreover, the current process of transcribing the returns manually by operators typing their contents into a computer is error-prone. About 22% of transcribed returns last year contained data transcription errors, Collins said.

2-D barcoding: Already in limited use

One of two methods Collins recommended, 2-D barcoding, is as time-honored and ubiquitous as most retail checkout lines and the 17 state departments of revenue that used it to process returns as of 20 years ago. Just as scanning a barcode on a retail product brings up all relevant details to a sale, one placed on a tax return by tax preparation software and printed out by the taxpayer for mailing can encode all information necessary for the taxing authority to process the return.

The IRS has in fact implemented 2-D barcoding for certain forms, including Schedules K-1, which are issued to partners of partnerships and shareholders of S corporations, reporting their shares of the entities’ income, deductions, credits, and other tax items.

Yet the technology’s potential for processing an entire return has been stymied by 20 years of dithering by the Service, Collins said. In 2002, when then-National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson, citing the example of the 17 states, recommended 2-D barcoding to the IRS, the IRS demurred, saying it could undermine taxpayers’ transition to e-filing.

A year later, however, the IRS began working with tax software companies to implement 2-D barcoding for some tax forms, such as Schedule K-1. The Service asked Congress in 2017 to provide its authority to require taxpayers filing paper returns prepared with software to use a 2-D barcode, which Congress initially included in an early version of the Taxpayer First Act.

But before the Taxpayer First Act’s enactment in 2019 (as P.L. 116-25), “the IRS had changed its position again,” ostensibly to give it more flexibility to use other scanning technology, and the provision was stricken from the bill’s enacted version at the IRS’s request, Collins said.

A Program Manager Technical Assistance memo (PMTA 2022-002) in December 2021 advised that the IRS currently lacks authority to require tax software developers to include barcodes, but the IRS can include one on its own tax returns and forms. The Service also can request that the software companies do so, Collins said. She directed that the IRS immediately begin discussing this with the companies in time for the 2023 filing season and if the companies decline to do so, to ask Congress to mandate it.

OCR: A backup to barcodes

The other main technology used for scanning paper documents is known as optical character recognition (OCR), which interprets the marks on a document and renders them into computer characters. While OCR has the advantage of also being able to read handwriting, it doesn’t always do so accurately, Collins said. Even so, some states use it in tandem with 2-D barcoding, such as when a barcode is smeared or otherwise unreadable, Collins said. She directed the IRS to also develop a plan to use OCR, also by the start of the 2023 filing season or, if not feasible by then, the following season.

The directive asks the IRS to respond to it by May 13, 2022, and state whether it plans to implement the directed actions, plans to implement alternative actions that will achieve the same objective, or declines to take the directed actions. If the IRS indicates it will implement the directed actions, the directive also asks the IRS to provide a detailed plan by May 31 to implement the two technologies for the 2023 filing season.