Billions of dollars earmarked for takeovers by blank-check companies have piled up unused as the hot-then-not mania fades for speculative stocks.

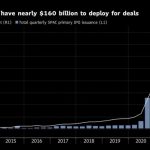

Almost 600 special-purpose acquisition companies holding nearly $160 billion in trust are searching for something to buy, data compiled by Boardroom Alpha show.

That marks a more than seven-fold jump for SPACs from the same period in 2020, and the clock is ticking against them. SPACs typically get a short window to either buy something with the money they raise — 12 to 18 months plus brief extensions — or else return the money to investors.

With about 88 active SPACs set to expire this year and another 318 facing deadlines in next year’s first half, there’s a “possibility of a logjam of deal closures,” Goldman Sachs analyst David Kostin wrote in a note.

Finding willing and worthy merger partners may be harder, now that the market for SPACs has turned from boom to bust, with some on Wall Street calling the craze “over.” The IPOX SPAC Index, which tracks SPACs and the companies they take public, is down 42% since mid-February, while the De-SPAC Index of companies that completed a merger has wiped out nearly two-thirds of its value.

The median de-SPAC in Goldman’s separate universe dropped by 43% in the past six months. The dismal performance can be explained partly by a low share float and the general lack of profitability, Kostin writes. About a fifth of de-SPACs were profitable over the past year and consensus forecasts show just 28% will make money in the year ahead.