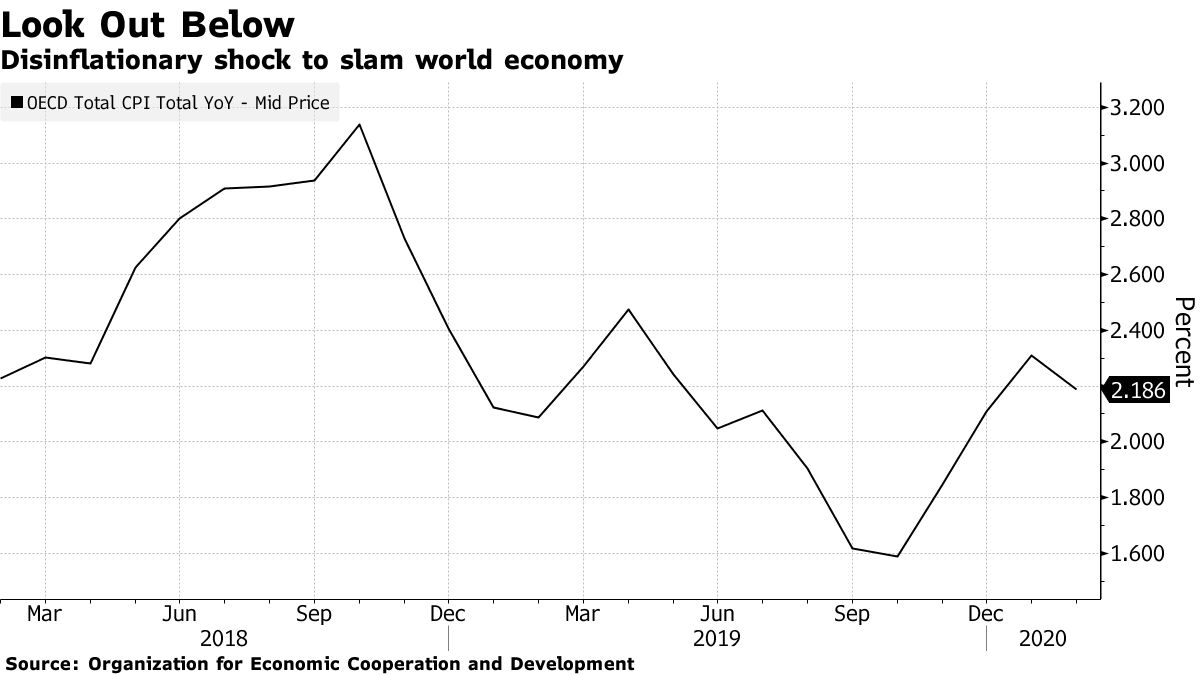

The sinking global economy is suffering through a colossal disinflationary shock that could briefly push it into dangerous deflation territory for the first time in decades.

With many national economies all but shutting down in an effort to contain the coronavirus, prices on everything from oil and copper to hotel rooms and restaurant take-out are tumbling.

“A powerful disinflationary tide is now rising,” said Joseph Lupton, global economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

That’s worrying because it could lengthen what may be the deepest recession since the Great Depression. Ebbing pricing power makes it harder for companies that piled on debt in the good times to meet their obligations. This could prompt them to make additional cuts in payrolls and investment or even default on their debts and go bankrupt.

While weak or falling prices may seem like an unalloyed good for consumers, a widespread deflationary price decline can be deleterious for the whole economy. Households hold off buying in anticipation of ever lower prices, and companies postpone investments because they see limited profit opportunities.

Even after the coronavirus crisis eases, the scars from the shutdown — elevated unemployment, shattered consumer and company confidence, and staggered returns to work — may keep price pressures in check, prompting central banks to hold interest rates at rock-bottom levels for a protracted period.

“They’re at zero for at least the next two years,” Ethan Harris, head of global economic research for Bank of America Corp., said of the Federal Reserve.

Monetary Largess

Further down the road, though, there’s a chance that all the monetary largess — coupled with a massive outpouring of government debt to pay for measures to fight the virus — could spawn a build-up in price pressures.

“It’s possible that the response to this over the longer term could have an inflationary consequence,” former New York Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Bill Dudley told an April 2 webinar organized by Princeton University. “But in the near term, it’s very definitely on the disinflationary/deflationary side.”

Lupton and his fellow JPMorgan economists forecast that their global consumer-price index will temporarily fall below its year-ago level sometime around the middle of 2020, the first time that’s happened in many decades.

Much of that is due to plunging oil prices. Even with their rebound last week on reports of potential production cutbacks, they’re still down about 55% since Jan. 1.

But other prices are also slipping, including for services. They have long been resistant to the downward tug that prices for internationally traded goods have been subject to, but now service-sector businesses are being slammed by the shutdowns. Lupton sees worldwide core inflation — excluding food and energy costs — falling below 1% and says there’s a risk it could stay there.

Disinflationary Force

“The overwhelming disinflationary force is quite large,” Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton in Chicago, told Bloomberg Radio on April 3.

While industrial countries — with the exception of Japan — avoided falling into deflation in the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis, they’re entering this one with inflation already at depressed levels.

Perhaps the world’s biggest source of deflation right now is China, where producer prices registered a 0.4% decline in February compared with a year ago after rising 0.1% in January. That’s a drag on the price of goods being shipped overseas from the world’s biggest trading nation.

But China isn’t the only country in pain.

Chain restaurants across Japan have rolled out discount plans for takeout menus, including Yoshinoya Co., which serves bowls of beef on rice and is running a 15%-off campaign.

Read more: Deflation a Real Risk for Japan, Former BOJ Economy Chief Says

The British Retail Consortium reported on April 1 that shop prices fell 0.8% in March, the biggest decline since May 2018, following a 0.6% February drop.

And in the U.S., domestic air fares plunged by an average of 14% between March 4 and March 7, according to booking site Hopper.com. Average revenue per hotel room plummeted 80% during the March 22-28 week from year-ago levels, hospitality-data firm STR reported.

“In terms of our business, COVID-19 is like nothing we’ve ever seen before,” Marriott International Inc. Chief Executive Officer Arne Sorenson said in March 19 video. “For a company that’s 92 years old, that’s borne witness to the Great Depression, World War II and many other economic and global crises, that’s saying something.”

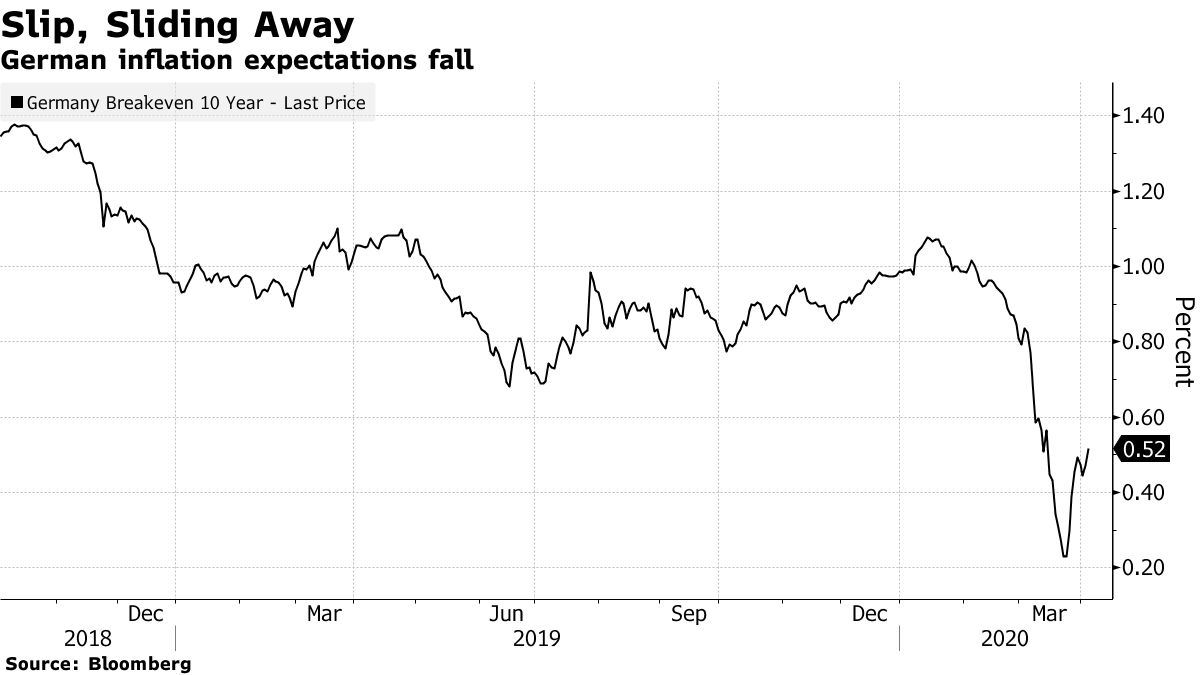

Investors seem to be looking for a long period of very low inflation, according to trading in inflation-protected securities, although some analysts caution the readings may be distorted by a dash for cash.

Even before the crisis, monetary-policy makers were worried inflation was too low for the good of their economies. Now they have even more reason for concern.

“Deflation cannot be ruled out, but I refuse to make an estimate,” European Central Bank Governing Council member Robert Holzman said. “If deflation is due to a slump in the real economy, it will be difficult to solve this through monetary-policy instruments alone.”

Some economists think it’s inflation, not deflation, that’s the problem.

“What will then happen as the lock down gets lifted and recovery ensues, following a period of massive fiscal and monetary expansion?” London School of Economics Emeritus Professor Charles Goodhart and Talking Heads Macroeconomics founder Manoj Pradhan wrote for VOX on March 27. “The answer, as in the aftermath of wars, will be a surge in inflation, quite likely more than 5% and even in the order of 10% in 2021.

Former chief White House economist Jason Furman said faster inflation should be welcomed, not worried about.

“I don’t think we should be afraid of getting inflation,” Furman, who is now a professor at Harvard University, told Bloomberg Radio on April 2. “If we get inflation that would be good. That would be a good sign that we have adequate demand.”

— With assistance by Christopher Condon, Sam Kim, and Yuko Takeo