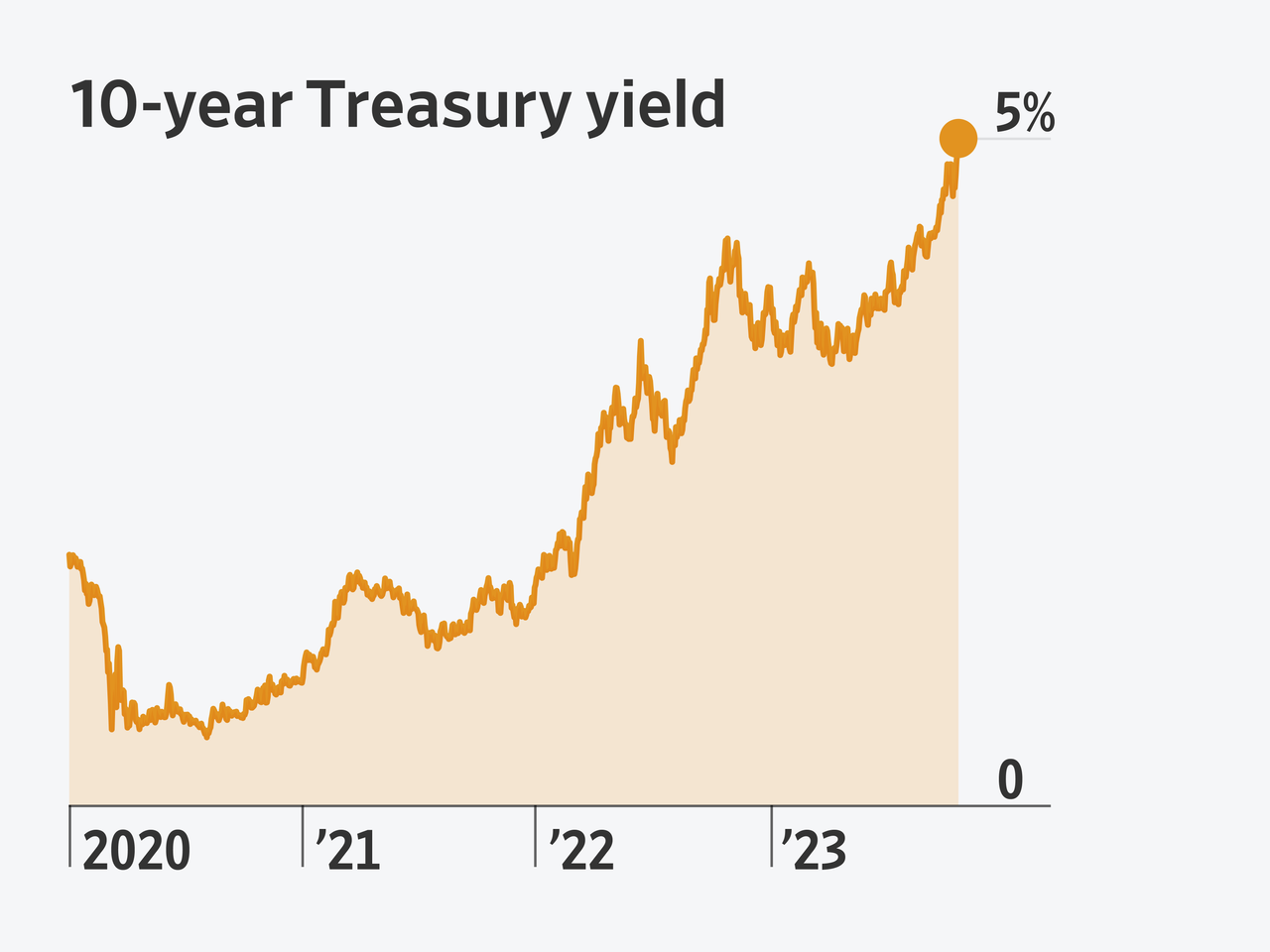

A deepening selloff in the U.S. bond market drove the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note to 5% for the first time in 16 years, marking a milestone that has rattled stocks, lifted mortgage rates, and fueled persistent fears of an economic slowdown.

A critical driver of U.S. borrowing costs, the 10-year yield rose as high as 5.021% in early morning trading on Monday, up from roughly 3.8% at the start of the year. It then reversed course and settled at 4.836% after the long-awaited breach of 5% stoked fresh buying interest.

Yields, which rise when bond prices fall, have climbed since the start of 2022, when investors began worrying in earnest that the Federal Reserve might raise interest rates to fight inflation.

In recent weeks, though, the selloff has only grown more intense and potentially destabilizing, with the 10-year yield jumping at times more than 0.1 percentage point a day and investors scrambling for explanations. The lack of clarity has only added to investors’ anxieties, reflected by declines in stocks that have pulled major indexes off their summer highs.

Many investors and analysts argue that high yields make sense given signs that a resilient U.S. economy can withstand much higher interest rates than previously believed. Investor expectations for higher rates drive down prices of Treasurys and push up yields because investors anticipate that new bonds will offer larger interest payments.

Others, though, worry that yields have become unmoored from the outlook for Fed policy and are responding to more unpredictable factors, such as souring sentiment about the size of the federal budget deficit and government’s willingness to address it.

The two theories imply different outcomes. If falling bond prices are justified by the strong economy, concerns about a 5% yield on the 10-year may prove just as fleeting as when the yield reached other milestones, dating back to early 2022 when it jumped to 2.5% from 1.5%.

If not, higher yields may finally lift borrowing costs to a point that businesses and consumers substantially pull back on spending.

“The question is: Is a 5% 10-year the type of number that breaks the U.S. economy?” said Scott Kimball, chief investment officer at Loop Capital Management. “Probably not, but you’re going to be in that yellow” caution zone, he added.

Investors and economists pay close attention to Treasury yields, and the 10-year yield in particular, because they set a floor on the interest rates across the economy, including those on mortgages and corporate debt.

For investors, yields also represent a risk-free return that they can get by holding government bonds to maturity—an important benchmark for determining the prices of riskier assets such as stocks.

A 5% 10-year yield is hardly unprecedented in U.S. history. But it was unthinkable to most investors just a few years ago, after a decade of sluggish inflation and ultraloose Fed policies, including near zero short-term interest rates and direct purchases of Treasurys.

The Covid-19 pandemic marked a turning point, leading to historic government stimulus programs, a surge in inflation and a different economy, marked by healthier private-sector balance sheets, changed work habits, and much higher rates.

Investors’ views of the economy have evolved gradually. At the start of this year, many expected yields to fall based on the assumption that they were already high enough to precipitate a recession.

Instead, growth has remained steady. And yields have generally kept rising, outside of a scare in March when the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank spurred fears of an imminent downturn. Yields also fell in the wake of Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack against Israel but have since picked up again.

For all the debate about what has fueled the latest, more acute selloff, most investors agree that the 10-year yield rose in the summer due largely to bets that interest rates would stay high for longer.

Investors had previously piled into wagers that the Fed would keep raising interest rates until it triggered a recession, and then start cutting rates significantly. That led investors to prefer longer-term Treasurys—holding their yields well below those of shorter-term ones in what is known on Wall Street as an inverted yield curve.

“The classic, very crowded trade was to own longer-duration fixed income, because typically in a recession bond yields go down and, if you own longer duration bonds, you make more money,” said Jim Caron, chief investment officer of the portfolio solutions group at Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

By the late summer, though, conditions were changing: inflation was cooling and the Fed was signaling that it was nearly done raising rates. Still, the economy, instead of sputtering, was showing signs of accelerating.

The result was a massive reversal in investor positioning, with longer-term Treasurys falling out of favor along with recession bets. Yields on those bonds shot higher, closing the gap with short-term yields.

Meanwhile, other potential challenges have emerged.

At the end of July, the Treasury Department announced that it would need to borrow more in the coming months than investors had been anticipating, leading to a larger-than-expected increase in the size of short and long-term Treasury debt auctions. The following day, Fitch Ratings downgraded the U.S. credit rating to just below triple-A, citing a worsening budget outlook and governance concerns, highlighted by standoffs over lifting the federal debt ceiling.

Since then, the rise in Treasury yields has only further fed anxieties about the budget, given that higher yields mean the government needs to spend more on interest payments. And Washington has continued to show signs of dysfunction, narrowly averting a government shutdown in a short-term budget deal that resulted in the ouster of Kevin McCarthy as House speaker.

Those types of developments are all helping to push yields higher, as investors balk at the prospect of ever larger Treasurys issuance, said Kimball, of Loop.

“Whether the government wants to admit it or not, the U.S. Treasury is now more double-A than it is triple-A,” he said.

Supporting the argument that a growing volume of Treasurys is feeding the bond selloff, some widely-tracked financial models have suggested that Treasury yields have climbed in recent weeks not because interest-rate forecasts have changed but because of an increase in the so-called term premium. That category covers all possible factors other than baseline rate expectations, including uncertainty about the rate outlook and supply-demand dynamics.

The question of what is moving Treasury yields is important because an uncontrolled bond selloff, removed from economic fundamentals, has the potential to be much more disruptive than an orderly rise in yields. A recent example is last year’s sharp declines in U.K government bonds that started when then Prime Minister Liz Truss proposed large tax cuts and only ended when Truss stepped down and the plans were scrapped.

Still, some investors say that alarm about the U.S. fiscal situation is overblown and not having a major impact on bonds.

Leah Traub, a portfolio manager at Lord Abbett, noted that government auctions of Treasurys have generally proceeded smoothly in recent weeks, with signs of less demand from overseas—where bond yields are also rising quickly—but increased demand from domestic buyers.

Traub is among those who have been wagering that the 10-year yield would rise. But her rationale has been that it will be difficult for inflation to fall all the way down to the Fed’s 2% target, causing the market to adjust to a higher path for rates.

“The labor market is still very, very tight,” she said. “And it would take a lot of economic weakness, a lot of growth weakness, to really have labor market weakness which would then feed into inflation coming lower.”